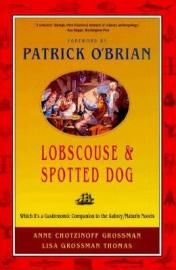

Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin novels (splendidly blogged by Jo Walton) have hived off a secondary industry almost as fecund as the Hary Potterverse. Eminent within it is Lobscouse and Spotted Dog, by Anne Chotzinoff Grossman and Lisa Grossman Thomas, with the subtitle, Which It’s a Gastronomic Companion to the Aubrey/Maturin Novels. Which it’s an attempt to cook almost all the food mentioned in the Aubrey/Maturin novels, by two New England ladies with true fananish zeal and a sprightly sense of fun, from skillygallee to salmagundy, from lobscouse (a stew) to Spotted Dog (a suet pudding).

You won’t get far in Patrick O’Brian’s series before you notice the food. Afloat or ashore, His Majesty’s Royal Navy honoured the arts of the table—whether the fare was Strasbourg Pie (an entire foie gras, wrapped in bacon, cooked in a pie) or pickled seal. Whether Captain Jack Aubrey dines alone, or in company of Stephen Maturin, or hosting a dinner for the offcers from the gun room, the table is the social centre of the ship. Many of the finest scenes and best dialogue takes place at the Captain’s Table.

Anne and Lisa’s grit in researching and preparing the recipes is truly naval. What obviously began as a bit of a culinary lark developed via a steely core and a horizon-eyed determination into a two year marathon involving everything from lab rats to smuggling breadfruit. All right thinking people are fascinated by food history—how much of our economic history is driven by food and drink—the spice routes, the golden cod, the impact of New World crops on the Old. It’s history ingested, in all its strange and sometimes shocking flavours and attitudes.

The books is divided along nautical lines: “The Captain’s Table” heads up the volume and is divided into “Breakfast” and “Dinner for the Officers.” “The Wardroom” and “The Gunroom” lead to the “Seamen’s Mess.” There are recipes for Jack afloat and Jack ashore and Jack “in durance vile,” when held prisoner. There are Stephen’s recipes from the Sick-Bay, including the famous “Portable Soup.” There are recipes from India and the Ottoman Empire. All is thorough and ship-shape. But this is much more than a collection of “receipts,” as recipes were known. There are relevant quotes from the novels, and from other well-researched historical works, from the Table of Proportion of Provision on His Majesty’s Ships to Hannah Glasse’s bloodthirsty receipt for Turtle the West Indian Way (“cut its throat or head off”). There are songs and music and menu suggestions, should you wish to host a Patrick O’Brian evening. (And why should you not?) There are poems and alternate receipts. There is an entire chapter on “millers”: rats, to you and me. Our ladies fearlessly prepared, cooked and ate “Millers in Onion Sauce,” and pronounced them very good indeed. Only the dullest of people could fail to be entertained by this book.

My copy of the book tends to fall open at “A Glass of Wine With You, Sir.” The amount of drink swallowed in the Napoleonic era navy is daunting to our lily-livered 21st century sensibilities. The daily allowance of grog was an eighth of a pint, twice daily, mixed 3:1 with water. (Navy rum was a liver-shrivelling 95% proof.) Ships went into battle nine sheets to the wind. Indeed, given the state of drinking water and the comparative safety of small beer and other alcoholic beverages, much of history seems to have been made by the half-hammered. In addition to a list of the finest wines available to (early 19th century) humanity, this chapter contains the shrubs, flips, grogs, punches and neguses—the Lemonade Heightened with Marsala is delicious and refreshing—and eminently makeable and quaffable. The recipe which gave the authors the greatest problem was the arrack-punch. The quest for arrack (I myself have had pretty good coconut arrack from Sri Lanka.) leads to a recipe from Mary Randolph’s Virgina Housewife for a “substitute for arrack” involving Flowers of Benzoin. Undeterred, our gastronauts give it a try:

…after many vicissitudes and humiliations we obtained (through means which we dare not reveal) a small amount of tincture of benzoin—which we are happy to report is not actually poisonous, though it does contain traces of a few “controlled” substances.

This sense of mischievous glee runs throughout the book and is one of its chief joys. This is cookery as an extreme sport. Here are two alternative methods—after a long discourse on the history of hard tack—of making ship’s biscuit:

…in direct contravention of all traditional methods, we have discovered two excellent alternatives to the arduous process of beating the dough. One is to run it repeatedly through a hand-cranked pasta machine; the other, much more exciting though a bit less efficient, is to put it in a large stout bag and repeatedly drive a car over it.

Those three words, “much more exciting,” light up every page. Anne and Lisa’s spirit of adventure only fails at one hurdle; “Boiled Shit,” which Stephen subsisted on when stranded in H.M.S. Surprise. Nevertheless, the receipt is duly given:

1 ounce assorted bird guano, ¼ cup rainwater. Gather the guano into a large clam shell. Gradually add the water, stirring constantly. Set in the hot sun until it boils. Do not drink unless absolutely desperate. Serves 1.

This is a delightful book. Even if you never prepare a single recipe, it casts a whole new light on a well-documented historical era, and is, as advertised, a gastronomic companion to those most gastronomic of novels, the Aubrey/Maturin books. Me, I’m off for some Voluptuous Little Pies and a glass of the Right Nantz.

Ian McDonald is the author of many science fiction novels, including The Dervish House, Brasyl, River of Gods, Cyberabad Days, Desolation Road, King of Morning, Queen of Day, Out on Blue Six, Chaga, and Kirinya. He lives in Belfast, Northern Ireland and can be found online at ianmcdonald.livejournal.com.

Just a hearty “Here here good sir!”

This book is

a)hilarious and amazing,

b)one of a few good books about military cooking in ye olden days, and

c)a perfect gift for someone who liked the books as most have never heard of this one.

I suggest purchasing it toot sweet.

Thanks for alerting me to this book! It sounds great. I was talking up the idea to my family all Thanksgiving. It’s now on my wishlist, so we’ll see what comes of it…

Was recently given the book by my Mother as she had found I was reading the Obrien series and discovered the authors were the Mother and daughter of the family who lived next to us 45+ years ago….Wonderfully fun and would ever so much like to get back in touch with Lisa…..So sorry to hear of her Mother’s passing… A marvellous read, NOT any poser type cook book AT ALL! The zest and fun exudes throughout!

I delighted in reading all O’Brian’s Aubrey-Matgurin books, and somewhere along the way, possibly this cookbook you write about, I obtained recipes for raspberry shrub (and lemon too, I think). I focused on the raspberry and in fact just made it, bottled it and put it in our (cool) garage, to sit for at least a week.

here’s my question: is it consumed like an after dinner drink? a liqueur? or is it diluted with water (a la the Colonial shrubs)? and I’d also so love to be reminded of which book contains a scene w/ the two friends enjoying shrub. (Is there a compendium for O’Brian yet?)

thanks to anyone who can help here!

Pat

Hi

I’m currently preparing my thesis for my Masters in Maritime History at Greenwich Maritime Institute. Iam looking at History as Fiction & Fiction as History with the emphasis being on the way Midshipmen supplemented their diets during the late 18th and early 19th centuries hence the title being: ‘Rats for Dinner’.

Which brings me to Millers in Onion Sauce……….Many references to millers but have the authors used their own recipe for the onion sauce or have I missed this somewhere in the Aubrey/Maturin series?

Hope somebody can help.

Cheers

ian